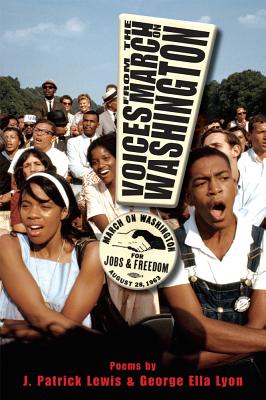

First off, congrats! Voices from the March on Washington is fantastic! Can you tell us how you got the idea for this book?

JPL: All credit goes to George Ella. When we first met at the Redlands (CA) conference a couple of years ago, I suggested to her that we might do a book together. She sweetly agreed and suggested the theme of Voices from the March. So we were off, and after many (many!) failed starts and later revisions, the book was finally born.

GEL: I came to this book through song. First I wanted to write about Kentuckian Mary Travers, who sang at the March as part of Peter, Paul & Mary. This morphed into writing about Travers, Odetta and Joan Baez. I hoped to explore how they became young women strong enough in themselves and their art to sing on the platform that day. In the process of researching them, I became fascinated with the March itself, and from that the idea for VOICES was born.

It’s one thing to write a fictional verse novel; it’s quite another to write an historical novel. How difficult was it to balance the fictional nature of the storyline with the history?

It’s one thing to write a fictional verse novel; it’s quite another to write an historical novel. How difficult was it to balance the fictional nature of the storyline with the history?

JPL: Despite its being mostly fiction, Voices still required significant research to get the facts right and to make sure our evocations were true to black culture. That was no easy feat for two white poets. But we both relished the challenge. A fictional account, told in different imaginary voices, allowed us the scope to be as inventive as possible with what might have gone on in Marchers’ minds.

GEL: We never thought of this as a novel but as a crowd of voices, flowing and surging like that August crowd. I didn’t find it hard to balance the fictional and the historical because I was imagining out of and into the history. The characters grew from reading contemporary and retrospective accounts, watching film from the times, studying photographs, listening to music, trying to immerse myself in that day and what led up to it. I even dreamed about it.

How did you decide which historical characters to include as voices in the first-person poems? How did you come up with the backgrounds and voices of the fictional characters they created for the book?

JPL: In a word, imagination, the poet’s stock in trade. Considering that there were a quarter of a million “voices” at the March, I think it would have been surprising if George Ella and I had ended up writing similar poems about similar characters. We wanted to include a range of people based on gender, race, age, even political bias, to reflect what must have been an astonishing range of experiences. In the end, I like to think we succeeded.

GEL: The decision of which characters should become soloists was based on the advice of our editor, Rebecca Davis, who is both meticulous and visionary. She and Pat and I emailed and talked it through in conference calls. At one point, Pat and I thought she wanted five soloists from each of us, so we wrote for four more main characters than the book has now. Some of those poems were reworked as other speakers. Some were thrown back into the hopper (wherever that is). We knew all along that we’d have to write more poems than we needed to get the best work.

Each of my poems has a tie to something that really happened. I most likely read about it, but I may have seen it. For example, Dan Cantrell’s poem “Tree” came from a moment in a film clip you can see on Youtube when Roy Wilkins says he wants to hear from, not just the people on the Mall but the people under the trees. “There are even some in the trees,” he says, and the camera pans to show us a young white man in the crown of a tree, holding his sign. (Here’s the Youtube link. Start at 13:30.)

Dan is from Dillard, Georgia, because I wrote part of this book there when I had a fellowship to the Hambidge Center for the Arts. Mr. Osage is named for the Osage produce market there, etc.

What was it like to write this collection with another author? Did you do anything different, individually, from other collections you’ve written?

What was it like to write this collection with another author? Did you do anything different, individually, from other collections you’ve written?

JPL: In short, delightful, while at the same time being enormously difficult. I mean by that the subject matter, of course, not working with George Ella. She was a dream partner. Since I’ve done a dozen “collaborative” books with other poets, the experience was not new for me, and not entirely different from working alone.

GEL: It was fabulous writing with Pat. I’ve never worked this way before. I’ve collaborated with directors and actors and musicians on plays I’ve written, but in those instances the words were all mine, so that’s a very different way to work. And in the picture book experience, I write the text and then the art director and editor work with the illustrator. The resulting creation is collaborative but it’s not an interactive collaboration between me and the artist.

Pat’s high energy, prolific poem-making was an inspiration, as was his knowledge about the time and events we were writing about. While I was sometimes mired in doubt, he was doubtless, and that helped me get past those snags. It was wonderful to be able to email poems back & forth and to receive his immediate and helpful response. Writing is usually a lonely undertaking and VOICES, appropriately, was not lonely at all. I loved it.

If you don’t mind telling us, what are you working on next?

JPL: I’ve just finished a collection of ekphrastic poems, that is, poems written to classic paintings. It’s to be called simply BLUE, given that the paintings are predominately blue. I’ve also recently submitted a third anthology proposal to National Geographic, which did my Book of Animal Poetry and the forthcoming Book of Nature Poetry (October 2015 with NGS photos). This one is tentatively titled The United States of Poetry, which will include solicited poems about the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

GEL: I have a novel for adults (my second) that is just going out to publishers and three possible picture books on my desk. And I am always working on poems.

Thanks to both of you! Be sure to follow Patrick at his website and George Ella at her website.